It is a legal requirement that anybody working with children, young people or vulnerable adults is appropriately briefed on safeguarding. As such it is important that all EdLab students engage with this post carefully.

By its very nature your work in EdLab will put you in contact with external partners and individuals outside the university – and often, these will be children and young people. Whilst you should never be put in a position by which you are responsible for a group of children, it is important that you appropriate briefed and considerate of the responsibilities this brings to you for child protection, and more broadly for ethical and professional conduct.

Safeguarding

The term ‘safeguarding’ is used to describe the processes and measures which are put in place in order to protect children, young people and vulnerable adults. This protection includes, of course, extreme instances of abuse and maltreatment – and the current legal framework was put in place in response to highly publicised failures of public bodies to respond to warning signs that children were in danger. Safeguarding does mean something a bit broader, though. The UK Government defines the term as;

‘The process of protecting children from abuse or neglect, preventing impairment of their health and development, and ensuring they are growing up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care that enables children to have optimum life chances and enter adulthood successfully.’

(DERA, 2014)

This extends the reach of safeguarding beyond child protection to incorporate the additional aims of preventing adverse impacts on health and development, and the promotion of circumstances is which children can thrive through to adult life.

Responsibility to assure safeguarding lies with both organisations (in our case, with the university through EdLab) and individuals (your project coordinator and, importantly, you). There are some basic implications of safeguarding policy for you. These are very simple, and should not be complicated;

- It is important that all EdLab students have completed a full DBS check. It is your responsibility to ensure that you have one, and our responsiblity to pay for it and to limit access to outreach activity without one. In rare situations in which it isn’t possible to gain a DBS (for some international students) alternative arrangements will be made for the student

- At no point should an EdLab student be left in sole responsibility – the lead for the space you are working in should be the project coordinator, a class teacher or equivalent or the parents of children (who should remain with them at all times

- If you are concerned, tell your project coordinator. One of the golden rules of safeguarding is that communication is important, and you should flag up any concern (even if you think it might be silly) about young people you are working with immediately with your project coordinator (let them decide whether further action should be taken). It is important to remember that there is no right to confedentiality in law … if a young person starts to disclose something to you, tell them that you will have to tell somebody, and then do tell somebody else, even if they don’t disclose anything.

Risk Assessment

Whilst the guidance above ensures that you are compliant with fundamental safeguarding commitments, there are additional responsibilities which you should be aware of. Most notably, you are responsible for ensuring that any participants are kept safe within the activities that you run for them. Risk assessment can sometimes get caught up in slightly silly rhetoric, but the fundamentals are pretty simple. The usual process goes something like this…

- Identify all of the hazards associated with your work. This is anything which might feasibly pose perils to physical or psychological health.

- Consider which of these hazards constitute risks. Hazards only become risks if they are likely to occur, and if they would be unsafe if they did. This is the process by which you ensure your risk assessment is both effective and sensible, by identifying the things that are most likely to need planning for

- Finally, you should establish precautions which will be taken in order to prevent risks turning into genuine dangers. What will you do in order to minimise the danger posed by hazards?

Usually, risk assessments are recorded in forms that look something like this – and shared with everyone involved in running the activity.

Professional Conduct

Work on educational outreach projects also has broader implications in terms of your personal conduct. It hopefully goes without saying, but we expect you to behave in professional ways – it is very easy to accidentally damage external relationships if not, and this makes arranging future projects very difficult. Everybody involved, including the outside guests who attend your project work, understands that you may well be inexperienced and novice at ‘doing education’ – and nobody expects that things will be perfect. Equally, though, there is basic level of professional conduct which is expected of our students in how you conduct yourselves within your teams, and in your interactions with those outside the university. Critical to this is effective communication and reliability; other people are often relying on the work that you do, whether its your project team or guests who are attending your activities – and it is therefore critical that you meet your commitments and deadlines. It is also important that you keep communicating with your project team throughout the process … even if things are going entirely to plan.

Quality Assuring your Work

The final dimension of this blog post relates to the importance of taking every reasonable precaution to ensure that your activities and events run smoothly and effectively. As noted above, we don’t expect everything to always run as you expect (indeed, education rarely works like this!) – however there is an extent to which, with some careful though, you can plan for the unexpected. In lots of ways, this process mirrors that of safeguarding, in that it follows these steps (but focused on things that might disrupt the smooth-running of your work, rather than responding to danger)…

- Work out everything that could go wrong when your run your activity.

- Audit each hazard in terms of how likely it is to go wrong, and how damaging it would be if it did.

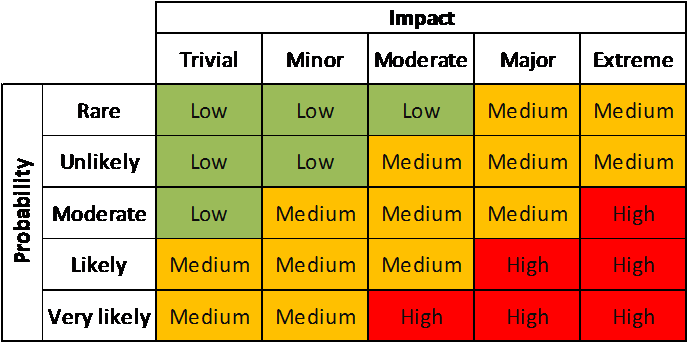

You can then prioritise responses according to this framework:

… In which you would have very definite fall-back plans to respond to anything red (high likelihood and high impact), and be aware of the possibility of anything yellow. The stuff in green, can be fairly safely deprioritised to give more space to focus on the more risky stuff.